#Basics of Neural Networks and Deep Learning - Part 1

Course Overview: Deep Learning Course - Overview

In this course, we will learn the basic theory of how our brain works and how artificial neurons (=> Perceptrons) imitate it.

#Content of this "Block"

i.e. the next few articles, the marked one is the current article.

- Our Brain and the Perceptron

- MNIST, and why good data is so important

- Structure of a Neural Network

- A Neural Network is learning

- Backpropagation

#How does our Brain work?

The first question here is, why is our brain even worth looking at?

Well, it is evolutionary optimized for solving specific problems. We can for example distinguish quite good between a dog and a cat (usually). On the other side, we are really bad in for example maths, because we never had the need to develop math skills in our evolution.

If we want computers to be superior in recognizing dogs/cats, we have to "imitate" our brain. For this we need to know how it looks and works first.

Our brain consists of millions of neurons, so it is basically a big biological neuronal network.

The network of neurons in our brain is called "Neuronal" Network, while artificial networks are called "Neural" Networks.

As the whole brain is a very complex system, let's look at neurons first:

Neurons take input signals, and give an output signal, if the sum of the input signal crosses a Threshold.

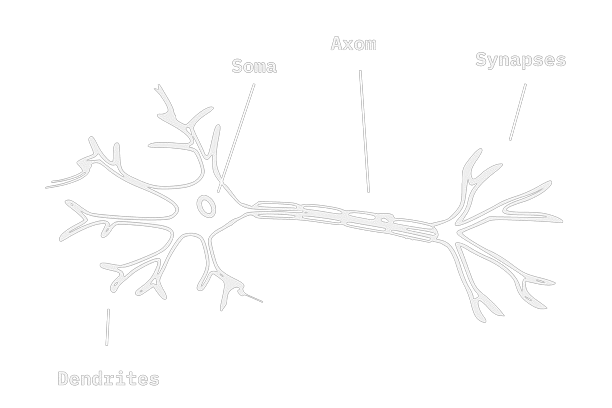

One single neuron looks something like that:

It consists of three (or four) main parts, that are important for us:

- Dendrites

- Axom

- Soma

- (Synapses)

The synapses are basically just the connection of one neurons axom to another neurons dendrites.

The dendrites take the "input signal". They are connected to other neurons through synapses, and when these neurons are firering (= giving an output signal), our neuron receives these signals over the dendrites.

The axom is the part of the neuron, that transports the "output signal" to the dendrites or synapses of other neurons.

The Soma is the centrum of the neuron, it's the place where all the input signal are collected, and where the output signal starts, when the input signals crosses a specific value. (A little bit simplifing biological facts)

#First Models of Neurons

Now that we know how the neurons in our brain work, we gotta write code, that imitates neurons. For this we have to look at more abstract models of neurons first.

The perceptron is such a model, developed by Frank Rosenblatt in 1958. It was heavily based on the McCulloch-Pitts neuron.

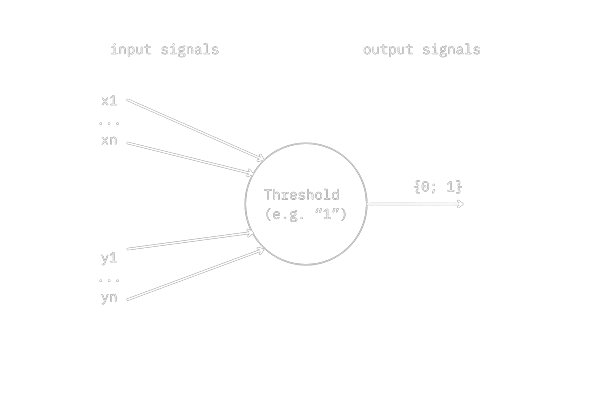

The perceptron in this model has x₁ ... xₙ stimulating input signals, and y₁ ... yₙ suppressing input signals (the exact amount is determined by the problem we try to solve).

Binary system

We'll use the binary system here. Just in case you don't know it, I'll explain it real quick. In the binary system (originally used for computers), we have only zeros and ones. This is because communication in and between computers is using electricity. The easiest transmittable format we can convert the data to is the binary system: we have only zeros and ones, representing no electricity (0) versus electricity (1).

In our case (and many others too):

1=true

0=falseThis should be everything we need for this course, but I'll maybe add an little article about the binary and hexadecimal system, and add the link here when done, if you're interested and want to know more.

In our perceptron, the soma is represented by a threshold, a value that determines when the neuron will fire:

- As soon as we have one (or more) suppressing signals, the output is always

0(i.e. stimulating signals are ignored) - If the sum of stimulating signals is equal or bigger than the Threshold, the output is

1 - If the sum of stimulating signals is less than the Threshold, the output is

0

In the following I'll call stimulating input signals just input signals, because usually most of the input signals are stimulating.

Our last component in the model is the output signal.

In this model, the input and output signals are binary (i.e. either 0 (=false)

or 1 (=true)).

This is still quite a simple and minimalistic perceptron. For further reading you can check out: What the hell is Perceptron?

Back to our perceptron: we can already solve some easy problems with this minimalistic thing 🥳.

As a "developer", lets try logic gates:

If you dont know what logic gates are, please take a look into it: Logic Gates. The Wikipedia article is quite good too.

#1. AND (two input signals, one output)

AND returns

true(=1) when both input signal aretrue, andfalse(=0) if one or both of the input signals arefalse.Input x₁ AND input x₂ have to be

true(1) to returntrue(1)

In a table, this would look like this:

| input 1 | input 2 | output |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

The AND function is solveable with a perceptron. We'll just set the threshold to 2. Now we have a few possible constellations:

- both input signals are

0-> sum =0-> the output of our neuron is0 - one of the input signals is

0, the other1-> sum =1-> our neuron returns0(the sum1is still smaller than our Threshold (2)) - both input signals are

1-> sum =2-> the output is1(because sum >= Threshold)

#2. OR (two input signals, one output)

OR returns

truewhen one or both of the two input signals aretrue, andfalseif both of the input signals arefalse.Input x₁ OR input x₂ is

true.

| input 1 | input 2 | output |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

Threshold: 1

If we have one or two stimulating (=true or 1) inputs, the sum is bigger or equal to the threshold, and the output is true (1).

#3. NOT (one suppressing input signal, one output)

NOT returns

truewhen the input signal isfalse, andfalseif the input signal istrue, i.e. always the opposite of the input.The Input y₁ is NOT (equal to) the Output.

| input | output |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 |

Threshold: 0

Note that we have a supressing input signal here, i.e. when the input is 1,

the output has to be 0, because we have a supressing signal.

On the other hand, if the input signal is 0, i.e. we don't have a supressing signal,

the output will be 1, because additionally to no supressing signal,

the number of input signals (0) is bigger or equal to the threshold (0).

#3. XOR - exclusive OR (two input signals, one output)

XOR returns

truewhen one of the two input signals istrue, andfalseif both of the input signals arefalseor if both aretrue.Either input x₁ OR input x₂ is

true.

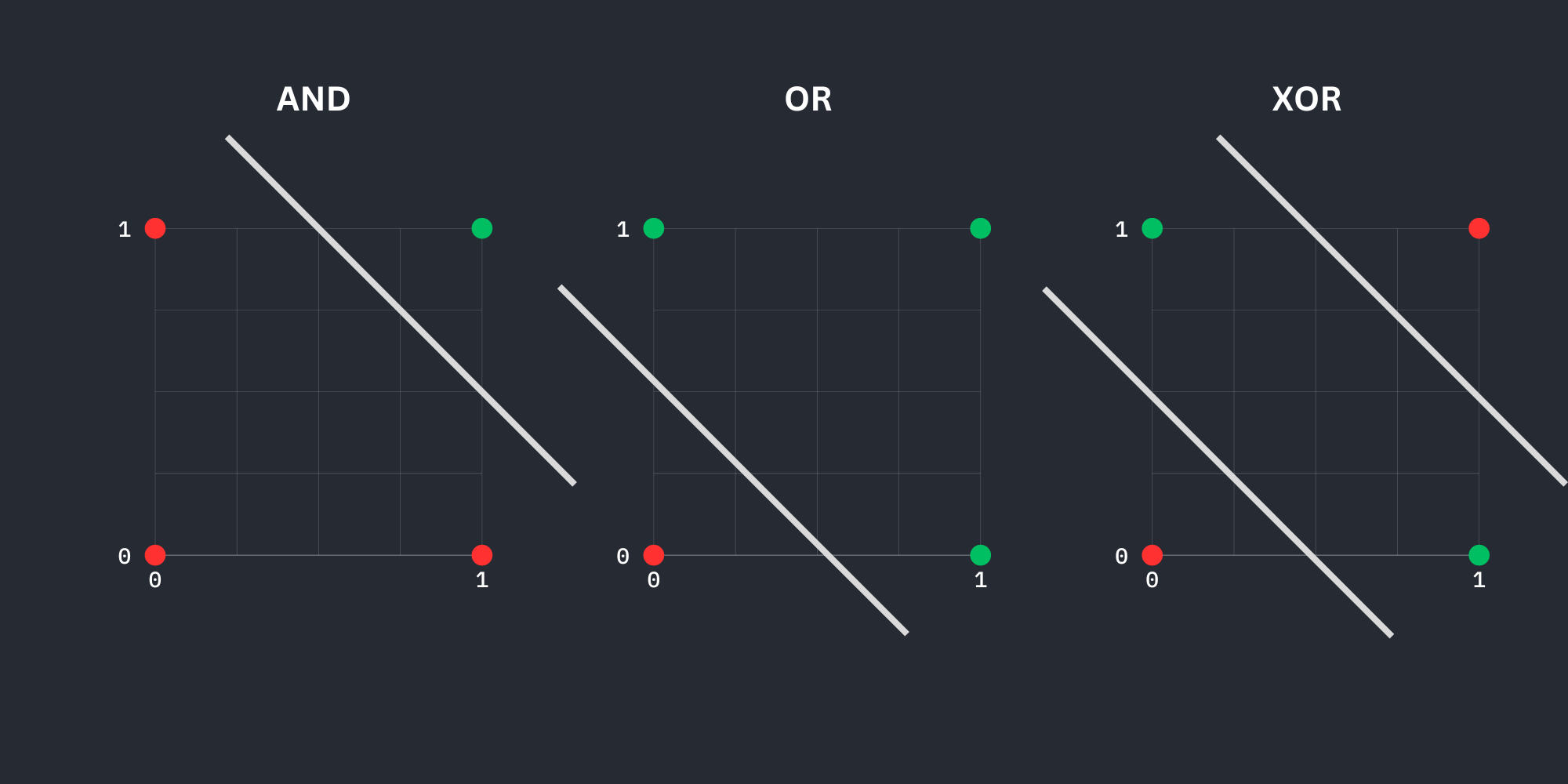

Here we'll run into a problem. This logic gate is not solveable with a perceptron.

Actually, this can be shown graphically.

(green dot -> return true; red -> false)

Here we can see, that XOR is not linearly separable, i.e. one single perceptron can't solve it.

However, if we take more than one perceptron / more layers, the XOR problem becomes solveable. What you should take away from that: every problem, regardless the complexity, can be solved with a finite number of perceptrons.

As you could see, we have set the thresholds manually in the examples. This is our next problem: getting the threshold values right for every singel perceptron. (usually they additionally have weights, and an activation function).

With bigger NN (a few million/billion neurons) this is very hard (=not possible), and that's why NNs need to be trained. During the training, they adjust the thresholds (i.e. we don't do this manually anymore), to get better and better results.

Little side note for those who don't know how an NN is trained:

You take data and label it (i.e. you match every data entry with the right solution). As we need much of this data, our only hope is usually that someone else has already done this (more about this when we come to MNIST).

Now we'll give the NN one data entry, and it will generate probabilities for all possbile solutions. It will suggest the most probable solution as the correct one. We compare this suggestion with the corresponding label, and tell the NN whether it was right or wrong.

Based on this, the NN adjusts the thresholds (using backpropagation, we will learn about this in a extra article).

Now that we know how a NN is learning, let's compare that to our brain real quick:

We are basically doing exactly the same thing (adjust thresholds of neurons), with the little difference, that the brain additionally adjusts the connections between neurons (topology).

#This is the End... (only of this article xD)

Well, it's already the end of part one. You hopefully learned how our brain works, and how Neural Networks try to imitate neurons, so we can start of with neural networks and their learning procces soon.

The next part will be a little bit smaller, we will learn about the MNIST dataset there. This part is quite important too, because we need to understand a little bit about good data for our first project.

Next Article: MNIST, and why good data is so important